How and Why she Wrote it

· “The Devil who Danced on the Water” (2002) is a classic example of a lyrical memoir.

· In terms of how it was written, she discusses how she wrote it using her memories including the fragmented ones from when she was a young girl, but that she required the use of interviews as a way of recollecting certain events that took place in Sierra Leone at the time of her father’s disappearance.

· She describes this process of remembering as being in almost concentric circles, placing her memories in the middle and then expanding to look at her father’s story then the history of Sierra Leone.

· Forna also notes that despite her turbulent relationship with her step-mother Yabome, that her cooperation for the book made it possible for her to unravel the true plot of the framing of her father.

· It is clear that her father has had a huge influence on her life and was her motivation for writing the book, with the first page of acknowledgements stating that “This book is dedicated to the memory of my father”.(vii)

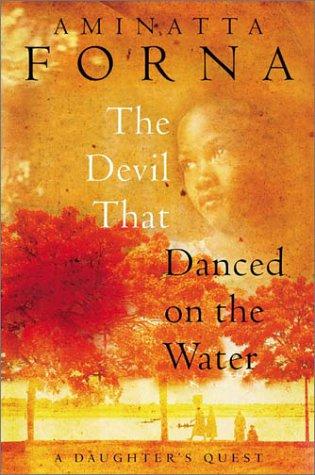

Picture 1

· The book is broken into two sections – book one and book two

· The first half of her story describes her father’s early life and his eventual migration to Aberdeen to study medicine. Most importantly, she discusses the fateful events that took place when her father was taken away for crimes he didn’t commit.

ð Her father Mohammed Forna trained as a doctor in Scotland, before returning to Sierra Leone to become one of the most well known men of the countries generation.

ð He was very involved in politics and promoting the rights of the poor; however, this had its repercussions, with Forna being arrested for alleged treason charges, that being the setting up of an opposition party.

· We first become aware of her struggle with the disappearance of her father when she describes the scene in which he is taken away:

ð “”I have to go with these two gentlemen now, Am...Tell Mum I’ll be back later.” These are the last words, the very last words he says to me”. (p14)

· The second half of the book sees Aminatta return to Sierra Leone as a journalist in her adult years, hoping to uncover what really happened to her father.

ð This can be seen as her attempting to gain closure for the past events, especially when she is impelled to track down the men who betrayed her father.

ð She also visits where her father’s remains are said to be buried.

· There is a longing to put at rest what really happened:

ð “Sometimes I dreamed he came back from living in a far away country, that he had been looking for us, but couldn’t find us...but despite the twenty-five years that had passed, they had never ceased entirely”. (p.17)

· “We could say that Forna set the record straight. Or that she made a detective story out of personal pain.” – Lorraine Adams, Washington Post.

The Voices in Book One and Book Two

- Forna split “The Devil That Dance on the Water” into two very distinctive parts, Book One and Book Two.

-

Picture 2 Book One contains a very childlike voice, that of Forna as a child and learning about the world around her, but veiled from the realities. We read about her experiencing childhood, focussing on what mattered to her, such as watching the ants, or being invited to a friends party, while bigger things she does not understand goes on around her. - Book Two is a journey of discovery, of finding new memories of her childhood. For example, Forna was convinced that it was her who fetched her father before he taken away, where in fact he was already on his way out on his way to meet those who were to take him away. Forna builds up a bank of memories, which she placed in “concentric circles”, allowing a build up of all the different memories, including her own, her parents, and those involved with her father's death.

- In the closing paragraph Forna says that the voice of the Book One is the one who believed the Devil could dance on the water, but through her investigations Forna's innocence is lost. If she tries hard enough she can regain some of the innocence of Book One, but she is forever changed by what she has learnt in Book Two.

Memory and Forgetting

- Memory is an important component of Aminatta Forna’s The Devil That Danced on the Water. Forna’s exploration of memory helps her understand her home nation and the history of her family, helping her establish a future by understanding the past.

- Memories, both personal and collective, form the frame of reference we all use to meaningfully interpret our past and present experiences and orient ourselves towards the future.

- The act of remembering is always contextual, a continuous process of recalling, interpreting and reconstructing the past in terms of the present and in light of an anticipated future.

- Aminatta Forna says: In the late 1990s, I began the process of collecting memories. The first memories I collected were my own. They were fragments from the first ten years of my life and they were memories of events that had taken place in Sierra Leone in my own family. But they had never been spoken about them, or at least, when they were spoken about it was only between my brother and sister and me. We talked about them in huddled whispers. But at the end of the 1990s and the end of the civil war in Sierra Leone, I decided that I wanted to go back and look at these memories and work at what they meant to us.

- In the memoir Forna writes: “All my life I have harboured memories, tried to place together scraps of truth and make sense of fragmented images. For as long as I can remember my world was one of parallel realities. There were official truths versus my private memories, the propaganda of history books against untold stories” (p.18)

- Forna is trying to put together the documented history of her country along with her own memories, the personal lives of Sierra Leoneans that are forgotten in history books.

- Forna is struggling to place her childhood identity inside the history of Africa: “I hoarded my recollections, guarding them safely against the lies: lies that hardened, spread and became ever more entrenched. Yet what use against the deceit of a state are the memories of a child?” (p.18)

- Forna says the process of writing a memoir “was one of remembering. Placing [her] own memories alongside the memories of others and the collective memories of a nation.

- She wants to assert her memories as fact and is frustrated as she realises that the widely accepted history of Sierra Leone will still stand up despite her childhood remembering.

- Forna continues to struggle with placing her memories into the history of Africa and also with memories of her family.

- A young Forna remembers ‘Lord of the Dance’ which she sings at school alongside her early days in Koidu: “It was the first time I had heard the song since our days in Koidu and I didn’t understand why the words and the tune were so familiar, or why I knew them by heart. I suddenly felt overwhelmed by the memory of my mother and instead of singing along with the others, I began to cry” (p.224)

- For reasons she does not understand a remembered song brings vivid memories of her mother and in her youth Forna does not know how to deal with the emotions this brings.

- Forna also struggles with her memories of Africa and what one of her school friends talks of: “I couldn’t seem to recognise any aspect of the Africa she described and I had begun to wonder if indeed I really came from there at all” (p.227)

- Forna begins to struggle with notions of home from this point in the memoir. Her memories tell her of a different Africa which is taught in England and she cannot link the two.

- This struggle with home continues into adulthood: “Sierra Leone to me was both utterly familiar and ineffably alien: I knew it but I could not claim to understand it” (p.271)

- Forna appears to be unable to connect the politics of her country with what she remembers of her time there. She cannot relate to Africa as her home.

- Forna also talks about forgetting. In reaction to her memoir she says that people would approach her and tell her they had asked their parents and grandparents: ‘Why did you never tell us that these things had happened when you knew all the time?’ And [their] elders shook their head and each one gave the same reply: ‘Because I made myself forget’.

- Forgetting or letting memories fade acts as a coping mechanism, a means of survival for those who experience something awful. In Forna’s case it was to survive the political climate of Sierra Leone.

- In her memoir Forna describes this: “There are those times when people hide something, or put some precious object away for safe-keeping or perhaps for discretion’s sake, and then forget where they have hidden it. Sometimes people forget about whatever it was entirely; then you hear how their children or grandchildren unearth the same item years on: a note folded into the pages of a book, a photograph tucked behind a mirror, a heart-shaped stone in a jar full of odds and ends. Memory, I discovered works the same way” (p.333)

- The process of forgetting is a way for the people involved to move on. Forna believes that Sierra Leoneans have reached a period in the aftermath of war and do want to forget, to get on with their lives, to plant their crops, to have children.

- Yet this forgetting allows those who were complicit in what caused such trauma are able to stay silent for longer.

|

| Picture 3 |

Race

We can see that throughout The Devil that Danced on the Water, Forna encounters the issue of her colour. One of the first times we see this is when she states:

“I refused to eat brown bread. … ‘Brown bread makes you brown and white bread makes you white,’” (p. 119)

Aminatta says this whilst in Aberdeen which makes us think that she was wanting to be white to fit in with the people around her. This was not the only time that Aminatta spoke about the colour of her skin.

Whilst at boarding school in England, Aminatta was unable to go to her best friends party despite everyone else in the class going.

“‘My dad doesn’t like black people. He told me he won’t have anybody black in his house. Sorry. Really’” (p. 231)

From a young age Forna could see how some people would treat her badly because of the colour of her skin.

Although, her dad was black, Aminatta‘s mother was white. Whilst attending school in Nigeria Aminatta is bullied by the other girls, when she tells her mother, her mother replies:

“‘I want you to remember that you are half white.’… ‘You’re better than those girls. Don’t you talk to or play with them’” (p. 146)

The way in which her mother says “half white” gives the impression that she believes that being white is better than being black which then in turn makes Aminatta better than those girls. When Aminatta went back to school she said that she “ostentatiously turned my nose up at the black girls.” (p. 147). Her mother’s attitude to these people clearly had an effect on Aminatta who never had a problem before being friends with “black girls”.

We can see through the book Forna sometimes struggles with the colour of her skin and the disadvantages that came with it in the time period. There are various references to race throughout Forna’s childhood however, they are not really mentioned in the latter part of the book. This could mean that as she got older she began to feel comfortable with her skin colour.

Bibliography

Brittain, Victoria; "The Truth About Daddy"; Review: The Devil That Danced on the Water; (The Guardian: 18th May 2002): http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2002/may/18/politics

Fallon, Helen; "My father my Country": http://eprints.nuim.ie/950/1/My_Father,_My_Country,_Africa_Jan-Feb_2005,_Vol_70,_No_1.pdf

Stock, Femke, 'Home and Memory' in Diasporas: Concepts, intersections, identities ed. by Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlan (London: Zed Books, 2010)

Fallon, Helen; "My father my Country": http://eprints.nuim.ie/950/1/My_Father,_My_Country,_Africa_Jan-Feb_2005,_Vol_70,_No_1.pdf

Stock, Femke, 'Home and Memory' in Diasporas: Concepts, intersections, identities ed. by Kim Knott and Sean McLoughlan (London: Zed Books, 2010)

'Memory and Forgetting: Aminatta Forna in Conversation & Valeriu Nicolae in Conversation', Index on Censorship, Vol. 35 No.2 (2006), pp.74-78

Aminatta Forna Official Website: http://www.aminattaforna.com/content.php?page=tdtdotw&f=2

Aminatta Forna Official Website: http://www.aminattaforna.com/content.php?page=tdtdotw&f=2

Picture 1: Aminatta Forna

http://belindaotas.com/?p=4427

Picture 2: Ants http://www.esa.org/esablog/research/from-the-community-army-ants-beard-microbes-and-ant-mimicking-jumping-spiders/

Picture 3: Aminatta Forna with her mother Maureen Campbell http://images.mirror.co.uk/upl/dailyrecord3/may2011/1/4/aminatta-forna-image-2-370620413.jpg

http://belindaotas.com/?p=4427

Picture 2: Ants http://www.esa.org/esablog/research/from-the-community-army-ants-beard-microbes-and-ant-mimicking-jumping-spiders/

Picture 3: Aminatta Forna with her mother Maureen Campbell http://images.mirror.co.uk/upl/dailyrecord3/may2011/1/4/aminatta-forna-image-2-370620413.jpg

No comments:

Post a Comment